The following text is from the book Creative Life: Music, Politics, People, and Machines, by Bob Ostertag. Published in 2009.

Note: a few years after the publication of Creative Life, Justin Bond the gay drag queen began identifying as transgender and adopted the name Justin Vivian Bond. The text below is presented as it was originally published in 2009. As Justin Vivian Bond, this artist has a breathtaking stream of accomplishments since 2009: books, movies, recordings, shows, and visual art.

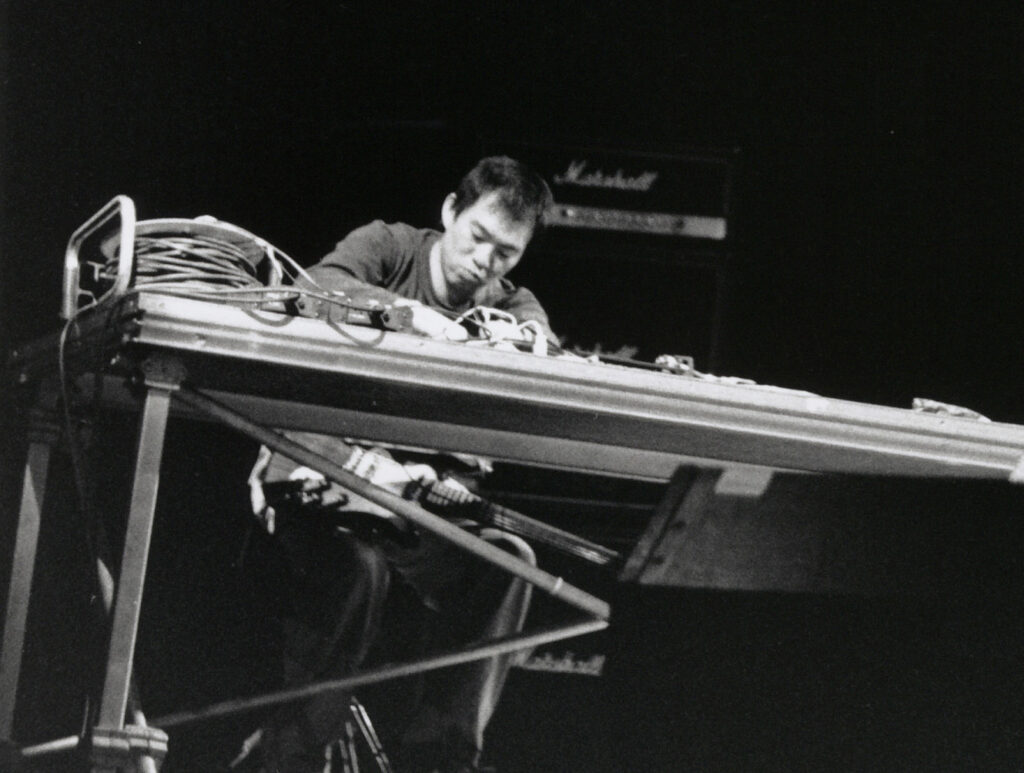

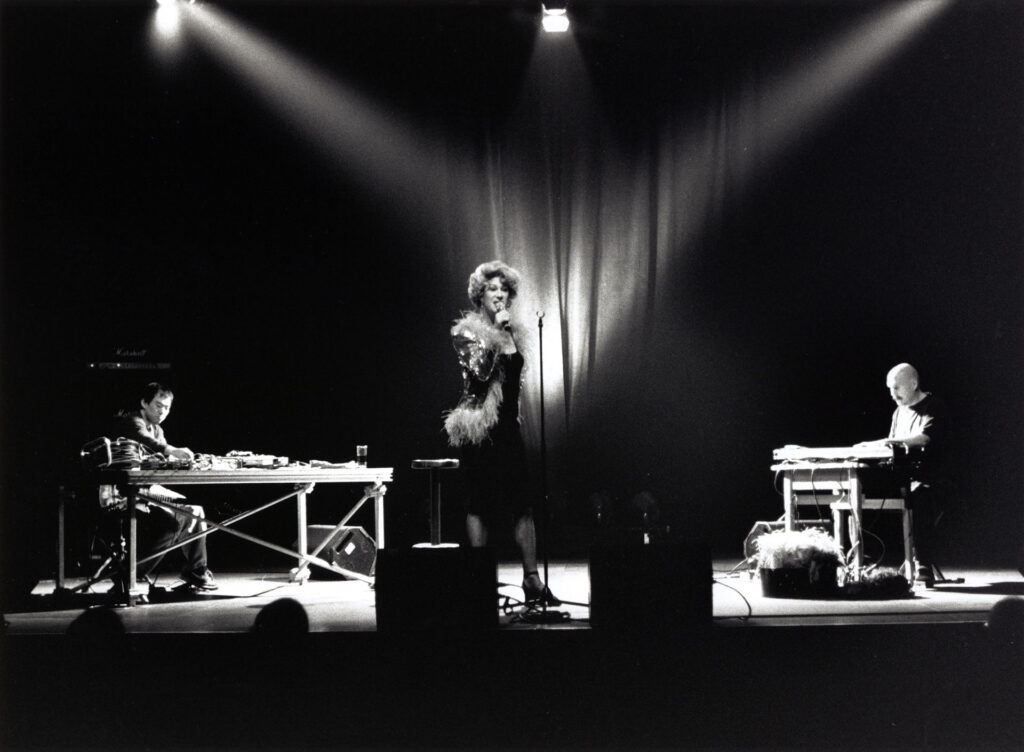

I have often felt fractured by the fact that while my colleagues in music and politics are overwhelmingly straight, my social world is predominantly queer. At times I have tried to address this by deliberately creating projects that would bring the two worlds together. Of all the people doing creative things in the queer community it has been my good fortune to meet, Justin Bond had a particular dazzle, and from time to time I would muse over what sort of project we might do together. There was no easy answer to this, as Justin does drag cabaret, and I do, well, all the things this book is about. Finally I decided maybe we should just go onstage together and see what happened. My friend Otomo Yoshihide, a sort of noise DJ from Tokyo with whom I occasionally did improvised gigs, was coming through San Francisco and asked me if I could set up a concert or two. I secured a venue in San Francisco (the Great American Music Hall, a five-thousand-square-foot nightclub built in 1907 with ornate balconies, soaring faux-marble columns, and elaborate ceiling frescoes), and arranged the show in two sets. The first set would be a trio of Otomo, myself, and Mike Patton, an extremely talented vocalist who at the time was alternating between fronting the platinum-selling heavy metal group Faith No More, his much more adventurous rock band Mr. Bungle, and fringe gigs of improvised music. The second set would feature Otomo, myself, and Justin. I called the two groups House of Discipline and House of Splendor.

At the time, I don’t think Justin had even heard any of my music, or any improvised music, for that matter. He had never met Otomo. But Justin was an improviser, no doubt about it. His cabaret shows were notorious for the sudden left turns and curveballs he would throw into the show when he forgot the words, or forgot where he was (there was generally a considerable amount of chemical enhancement in his performances), or simply because he felt like it. I had absolute confidence in Justin’s intuition. We did the concert without any rehearsal. I simply told Justin, “So, there will be the Japanese guy with turntables, and me with a sampler, and we are going to make a bunch of noise, and you just do drag: sing songs, dance, tell stories, do your makeup, anything you like.”

I should note that in addition to Justin being completely unfamiliar with this sort of performance, Otomo had had very little contact with queer culture or queer people. Gay culture in Japan is a pretty dreary place, largely hidden and full of sadness. There is no “queer” fringe to the subculture.

I should also note that Justin doesn’t really have to “do drag” in order to project gender ambiguity. He is an extremely effeminate man. Justin is one of those guys who, if he was ever in a place where his life depended on passing for straight, he would just have to die because there is simply no way Justin could ever pass for a straight man. It is out of his hands. Those are just the cards he was dealt. What makes Justin so special is that he was born not only with a generous helping of gender confusion, but with even larger servings of brains and talent.

The concert was one of the oddest nights I can remember. The hall was packed with Faith No More fans who had come to see their hero and had no idea what they were in for. They were already taken aback when the first set turned out to be a barrage of abstract sound, featuring Mike snarling wordless noises into busted microphones built into a podium originally designed for street-corner evangelists to power with car batteries. The audience had no forewarning that in the second set Mike would be replaced by a drag queen from another plane. Justin came onstage in a one-piece ladies’ swimsuit with a jar of indoor tanning lotion and announced he wanted to have a perfect tan before the end of the set.

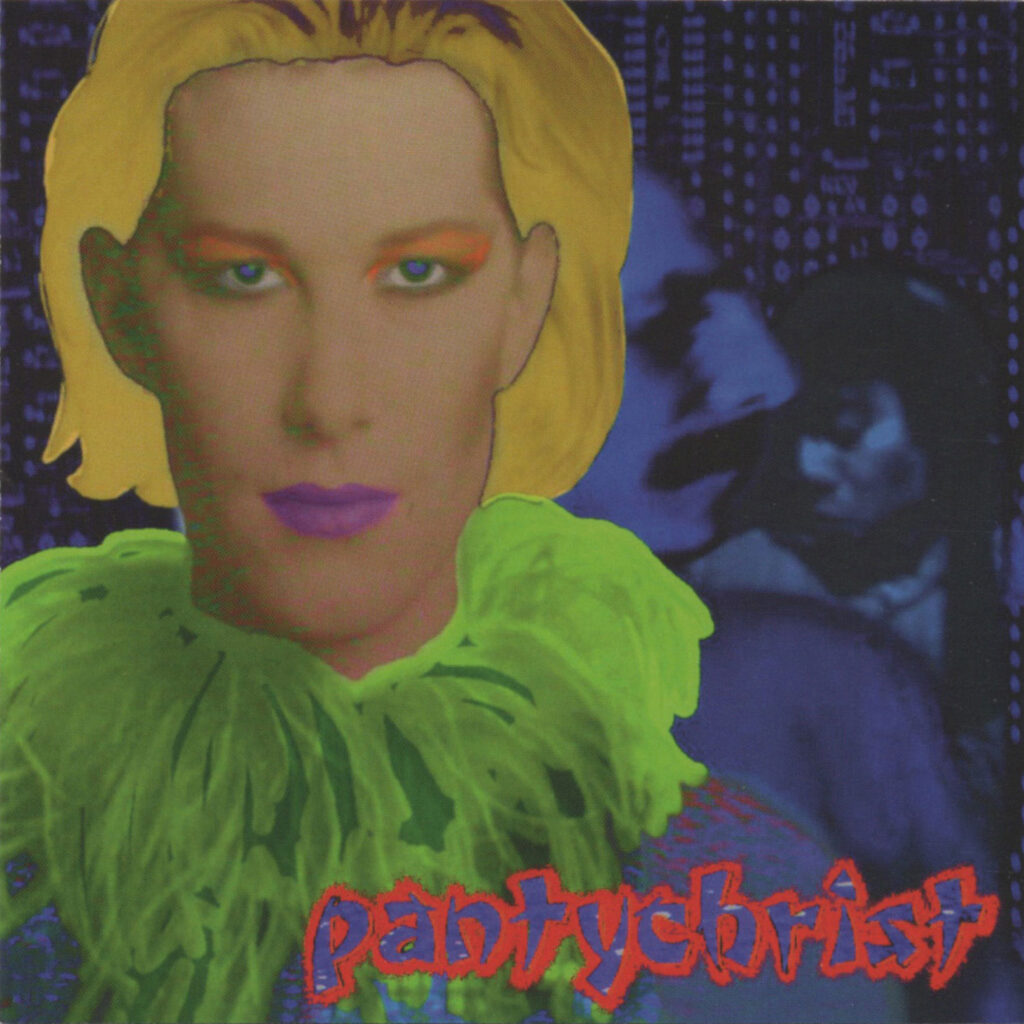

I think the audience was simply stunned. When we got back to the dressing room, Otomo, Justin, and I looked at each other and asked, “What was that? Was that pretty good or the worst thing we have ever done?” At that moment, for the only time in my life, a man from a record company burst in, beside himself with how great our show had been and gushing about how we had to make a record for his label right away. Thus was born PantyChrist. Or PC, for short.

The man was Naut Humon of the Asphodel label. With an advance from Asphodel, we booked another show and arranged to bring Otomo back from Tokyo and Justin back from New York, where he had recently moved. The idea was that we would do a live show one night and spend the following day in a recording studio. Everything would be improvised. After Otomo and Justin had left, I would take the tapes and see what sense I could make from the carnage.

The concert was fine, but the following morning I became extremely sick and spent the entire day in the hospital. I got home from the emergency room at about the same time Otomo, who was staying at my place, returned from the studio. I was quite curious about what had happened, particularly since Otomo spoke very limited English and Justin’s improvisations consisted largely of hilarious drag queen rants full of black humor and double entendres.

Bob: So, how did it go today?

Otomo: It was fine.

Bob: Could you understand what Justin was saying and singing?

Otomo: No, I understand nothing.

Bob: So, um, how did you decide what to play?

Otomo: I watch recording engineer through glass. When I see he laugh, I play something funny.

After Otomo and Justin had left, I took the hours of tape from the concert and studio session, cut them into little bits, and reassembled them into something that made vague sense. I then overdubbed a bunch of tracks of my own, adding a layer of connective tissue that imposed a sort of “song” structure on the whole thing. I then invited a few friends over, one at time, to add more tracks. (Jon Rose on violin, Richard Rogers on keyboard, Trevor Dunn on bass.) I didn’t really tell them much of anything about what the project was or what was on the tape. Instead, I simply told them to start playing right from the moment I hit “play,” to not stop until the end, and not to worry about wrong notes—there could be no “wrong” notes in this project. I then subjected these tracks also to the same slice-’n’-dice procedures I had used for the others.

When Asphodel received the tape, the owners of the label were ecstatic. One called to tell me that the reason she had gone in to the record business was to make recordings like this. Naut called to say they wanted to double the promotional budget. They wanted Justin’s address to send him a bouquet of flowers. And then, silence. Weeks went by. Finally, Naut called to say that Asphodel would not be releasing the recording at all. He explained that as the label had grown, the original two owners had brought in someone with more experience in the “biz,” and that this someone found our recording so offensive that he would quit the label if Asphodel released it. Naut felt so bad about it that he returned the master tape and told us to keep the advance, essentially telling us to take his money and go away. Record companies never give artists something for nothing, but apparently PantyChrist had blown the fuses at Asphodel.

Eventually we released the CD on Seeland, a micro label run by the media guerilla group Negativland. Almost no one bought it. We did a handful of shows in Europe: the Taktlos Festival in Switzerland and shows in Germany, Belgium, and Portugal. And then, as with most of my projects, I simply ran out of the energy it took to keep it alive. It was like pushing water uphill. Otomo didn’t want to do it anymore. I think he had never been fully comfortable onstage with someone as queer as Justin. And Justin himself was ambivalent. To my mind, PantyChrist was a way for Justin to escape from the “drag queen” box his cabaret act kept him in and move into a much more open-ended terrain. But PantyChrist was so far from his usual turf that I think Justin never felt fully at home there. And in the meantime his drag cabaret act, Kiki and Herb, had taken off. Kiki and Herb have now achieved celebrity status. They have sold out Carnegie Hall and had extended runs both on and off Broadway. Then Justin was cast as himself in John Cameron Mitchell’s feature film Shortbus. Justin is a star.

More than once, straight colleagues have told me that “if you are interested in being taken seriously as a composer, you don’t help your case any by working with drag queens.” But frankly, I don’t care. I still consider PantyChrist one of my most successful projects, bringing together disparate elements both social and musical into one organic whole that somehow makes sense yet is utterly odd. A critic who saw our only German concert wrote that it was “like seeing the entirety of American culture stuffed into 30 minutes.” A review in a gay zine wrote, “To say that this has made me radically rethink my use of the word ‘queer’ is an understatement.” From my perspective, this is the highest praise to which I might aspire, especially if one takes the word queer not in the limited sense of a gay subculture but in the broader sense of something so out of the ordinary that it startles the attention and piques the curiosity. In this sense, I would be happy if people had such a response to every project I have ever done.